In the early 1980s, when I was studying in the Uni, we used to go gaga about films made by three Bengali directors: Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak. Satyajit was elite, and like his tall physique and rich baritone much different from an average Bengali, his films used to come as if with a Post-it tag: No criticism please. Much like the films of Fellini, Goddard or Antonioni. Mrinal Sen used to attract for his left leanings (I was an active member of SFI at that time), and Ghatak mesmerized us for his bohemian life, and the use of unusual imageries in his films. That was the time when we were starry eyed, and used to strive to find out newer ways and superlatives to describe these films.

In the early 1980s, when I was studying in the Uni, we used to go gaga about films made by three Bengali directors: Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak. Satyajit was elite, and like his tall physique and rich baritone much different from an average Bengali, his films used to come as if with a Post-it tag: No criticism please. Much like the films of Fellini, Goddard or Antonioni. Mrinal Sen used to attract for his left leanings (I was an active member of SFI at that time), and Ghatak mesmerized us for his bohemian life, and the use of unusual imageries in his films. That was the time when we were starry eyed, and used to strive to find out newer ways and superlatives to describe these films.Today, when revisited, most of Satyajit Ray’s films appear to be living room drama, shots predictable and clichéd, sets a tad artificial. Mrinal Sen’s political films (that means nearly 90 per cent of his films) feel like Russian propaganda movies and are extremely boring. Ritwik’s films, on the other hand, appear still meaningful, dialogues potent, and imageries fresh and startling.

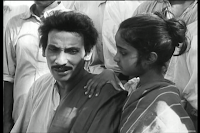

Subarnarekha impressed me again. The storyline is complex, but predictable, and Ghatak has thrown in too many coincidences into two hours of celluloid. Ishwar (Abhi Bhattacharjee), an educated unemployed takes break from the fights for their colony, and goes to Chhatimpur on Subarnarekha river, after a college friend offers him a job as cashier in his iron foundry. Ishwar takes with him his kid sister Sita (Madhabi Mukherjee) and an orphan Abhiram (Satindra Bhattacharya). Sita and Abhiram fall in love while playing at the riverbanks and singing songs in the forest, and elope as Ishwar makes arrangements for her marriage. Abhiram sees her estranged, low-caste mother die on the platform, and in Calcutta struggles to make ends meet. A child is born but Abhiram dies in an accident. Meanwhile, Ishwar takes to drinking. One day drunk and without vision (the specs break while drinking), Ishwar visits Sita’s house in search of further pleasures. Sita commits suicide. Two years later, Iswar is released as it is proved that it was suicide rather than murder. At the end, he takes Sita’s child to Chhatimpur, promising him a new house.

Subarnarekha impressed me again. The storyline is complex, but predictable, and Ghatak has thrown in too many coincidences into two hours of celluloid. Ishwar (Abhi Bhattacharjee), an educated unemployed takes break from the fights for their colony, and goes to Chhatimpur on Subarnarekha river, after a college friend offers him a job as cashier in his iron foundry. Ishwar takes with him his kid sister Sita (Madhabi Mukherjee) and an orphan Abhiram (Satindra Bhattacharya). Sita and Abhiram fall in love while playing at the riverbanks and singing songs in the forest, and elope as Ishwar makes arrangements for her marriage. Abhiram sees her estranged, low-caste mother die on the platform, and in Calcutta struggles to make ends meet. A child is born but Abhiram dies in an accident. Meanwhile, Ishwar takes to drinking. One day drunk and without vision (the specs break while drinking), Ishwar visits Sita’s house in search of further pleasures. Sita commits suicide. Two years later, Iswar is released as it is proved that it was suicide rather than murder. At the end, he takes Sita’s child to Chhatimpur, promising him a new house.‘Finding a new house’ has been the refrain of the movie—in the beginning we see the refugees trying to find a foothold, Sita comes with her brother to Chhatimpur in search of a new house, Abhiram searches his roots all his life, and the film ends with Sita’s son looking forward to a new house. But what I missed 25 years ago was the connection of this refrain with the title Subarnarekha.

Subarnarekha is the name of a river, and rivers cross unknown terrain on their way to find their ultimate home, the sea. While in spate, rivers wash away people’s abodes, pushing them to search for new dwellings; they also create new lands to help people settle. The name Subarnarekha (meaning golden thread or golden line) also denotes hope and prosperity that people look forward to in settled life.

The re-view of the film also made me think about Ritwik’s use of locale and imageries. Satyajit Roy used to be very fussy about the location of his films, and used to take a lot of time in searching them out. I remember an interesting story he once told. The shooting of Jalsaghar (The Music Room) was getting delayed as Satyajit was not being able to find out an old, dilapidated palace that would be appropriate for depicting the decadence in the movie. Finally, he found a huge mansion at Murshidabad, a little away from the river Ganges. Satyajit wrote to Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay (the writer of the story) about the house, requesting him to visit the palace once. Tarashankar wrote back, “But that is the palace on which my story is based on!”

However, Satyajit hardly strayed from his scripts, and avoided using new imageries and elements even if he found one in the location. That might be of the reasons of his films being so smooth, well-strung, and no-frills affair. Ritwik, befitting his Bohemian lifestyle, used the location to the hilt, and never thought twice before putting into new imageries and elements found in situ. Even if that needed making drastic changes in the script. And that gave a new dimension to his films.

While shooting Subarnarekha, Ritwik spent a lot of footage on the deserted World war II aerodrome that he found at the location. The abandoned airstrip became an integral part of Sita’s transition to womanhood, her affair with Abhiram, and her coming to terms with the dark side of life (facing a beggar dressed as Goddess Kali). In fact, the last imagery became the most talked about scene in the film. (In a recent film Sarisrip, Nabyendu Chattopadhyay also used the beggar dressing up as Kali incident, but the scene failed to give the goosebumps that Ghatak’s film gave.)

The narration of Subarnarekha has been too doctored at places: incidents fall into place like they never do in real life, and most characters talk in theatrical mode. In fact, that is why like most of Ghatak's films, Subarnarekha was totally rejected by the public. But I feel Subarnarekha is a classic and as an important landmark in the history of Indian Cinema. I would see the film again because the poignant passions that the characters portrayed, the exquisite imageries that Ghatak used, and as Sita in many occasions looks like my fiancé.

The narration of Subarnarekha has been too doctored at places: incidents fall into place like they never do in real life, and most characters talk in theatrical mode. In fact, that is why like most of Ghatak's films, Subarnarekha was totally rejected by the public. But I feel Subarnarekha is a classic and as an important landmark in the history of Indian Cinema. I would see the film again because the poignant passions that the characters portrayed, the exquisite imageries that Ghatak used, and as Sita in many occasions looks like my fiancé.Director: Ritwik Ghatak. 1965. Black and White